The Magic of the Better Software Conference

Why BSC worked; why other conferences don't.

The Death of Usenet

Usenet is a decentralized message board network created in 1980. Predating the World Wide Web’s ubiquity, Usenet was inhabited by a small and exclusive population from universities, laboratories, or other prestigious institutions. The general public originally didn’t know what it was, have the means to access it, or know why it mattered.

Even in simple text-based communication, humans build culture, norms, shared ideas, and etiquette. These are social technologies, developed to find and apply common purpose, maintain a standard of discussion quality, and share information efficiently. Usenet was no exception.

Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, at the beginning of each academic year, new university students would have their first opportunity to join Usenet. So, every September, existing Usenet users would notice an influx of “noobs”.

Noobs joined and disrupted culture. Training a noob to be familiar with a board’s shared ideas, etiquette, norms—and to be respectful of them—was not free. But given sufficient time, noobs would either assimilate or leave. Given the still-limited access—and given that it was limited to university students, an already exclusive (at the time) demographic—it was manageable to maintain the spirit of many boards, despite the yearly September influx.

This changed in 1993. Eternal September began when easy Usenet access was first offered to the general public by Internet Service Providers. Usenet boards—originally frequented, again, by university students, professors, engineers, scientists—were flooded by a large and seemingly permanent wave of noobs, sourced from a much larger and less exclusive demographic.

The masses of noobs were so large, and so culturally far, and in many cases so cognitively far from those who originally frequented boards, that moderation—and thus the preservation of board culture—became non-viable. Old-timers became outnumbered by noobs—their boards were no longer theirs. What was once a decentralized network of communication hubs for small, elite circles became much more representative of modern Internet boards—what you might see if you have the misfortune of taking a wrong turn while surfing the web.

I don’t remember Eternal September because I wasn’t born when it happened, let alone using a computer. But when I first learned about the shift it brought, I was intrigued, as I’d experienced something strikingly similar.

Other examples of similar cultural disruption beyond the Internet are not scarce. The CGDC of the 1990s is not the same as today’s GDC. The Bell Labs of the 1950s is not the same as today’s Nokia Bell Labs. The Apple of the 1990s is not the same as today’s Apple. The Microsoft of the 1990s is not the same as today’s Microsoft. The Google of the 1990s is not the same as today’s Google.

The Death of Google

In each case, what began as a selective, elite, high quality, productive, and revolutionary organization, ultimately sacrificed health for growth. This is not to dismiss the still brilliant individuals within any given organization—I mean to merely describe patterns at the granularity of the organizations themselves.

A microcosm of the same phenomenon can be seen in the conflict between early Google programmer Ben Gomes—who joined Google in 1999, and worked as a pivotal contributor to the early success of Google’s flagship Search product—and others, notably Prabhakar Raghavan—the “noob” who joined Google in 2012.

There was a fierce conflict between Gomes and others like Raghavan over the decision to intentionally degrade Search quality in favor of serving more advertisements to users—or, in other words, what users didn’t ask for—to provoke a larger number of queries.

There is perhaps no clearer example of the rise—in Gomes—and fall—in Raghavan—of the Google “Don’t Be Evil” motto. Gomes seemed to truly believe in the original spirit of Google, and felt that it was being corrupted by a lust for growth:

I've been thinking a bit about what Shashi says and I tend to agree that we are getting too close to the money.

[…]

I think it is good for us to aspire to query growth and to aspire to more users. But I think we are getting too involved with ads for the good of the product and company. We need to think of other issues like DuckDuckGo and the privacy challenge and our innovation narrative. We need to retain users for the long run.

[…]

I am getting concerned that growth is all we are thinking about.

Raghavan, on the other hand, was a noob—far removed from the original mission and spirit of Google, and far too focused on second-order spreadsheet metrics like “number of queries”—too depraved and soulless to understand that such metrics are downstream from spirit.

People Are Not Fungible

For any given example, it’s not difficult to find anecdotes from old-timers, where they nostalgically recall the old times, and lament what they feel was lost. The reason is clear: this is an undesirable phenomenon. More is not always better.

Individuals within larger and less exclusive populations have less in common with one another; there is less to bind them together. Reasons to form strong social bonds within the community have become informal, whereas in a highly selective group, the selection itself makes those reasons formal.

In the younger versions of these organizations, due to their more exclusive nature, meeting another person is refreshing. Upon meeting, you instantly know many deeply personal things you can bond over—shared passions, interests, hobbies, goals, philosophies. This makes friendships, partnerships, and information transfer both pleasant and efficient. In the aged versions of these organizations, one’s null hypothesis about commonalities between any two people change such that this is not true.

This phenomenon is driven by an organization’s age, and it seems to necessarily flow in one direction—towards the preference of growth, at the cost of exclusivity and cultural preservation. It’s unsurprising that companies, specifically, exhibit this effect—and ultimately regress towards the mean—because it reduces risk, and doesn’t immediately compromise profit. The longer a company is alive, the more incentive there will be to stop betting on the initial “magic” which made the company function to begin with (since it’ll inevitably die out regardless).

The more aged an organization, the more generic the bonds, the less exclusive the members, the larger the membership—and thus, a much higher social cost to change. It’s not popular to make an inclusive group exclusive. In many cases, it’s unclear how to do it at all. It destabilizes relationships, causes controversy, and poisons the air with conflict.

Put simply, in the long term, the quality of an organization can only diminish with time.

Therefore, the initial formulation of an organization—who is in it—is critical. Beyond that, the degree to which both exclusive selection and “noob training” continue to occur determines the organization’s age—or at least as long as it has until it deteriorates beyond recognition.

This is all for a simple reason: people are not fungible.

The Better Software Conference

The first Better Software Conference took place in July 2025. I had the privilege of giving a talk.

I arrived in Stockholm the day before conferencegoers were to meet. This gave me a chance to briefly explore the beautiful, historic city.

The next day, conferencegoers met up at the airport. We found ourselves on a four hour train ride to what seemed like the middle of Swedish nowhere. For many attendees including myself, this came after a long international flight to Sweden, so the extra travel might seem like it’d be exhausting.

Physically I was tired, without a doubt. But mentally, nobody seemed to be exhausted. Despite being comprised almost entirely of strangers, the whole four hours were filled by fun and fascinating conversations—which didn’t subside until the conference ended almost a week later.

We arrived in a charming small town, and were led by one of the organizers on a short walk from the train to the somewhat Twin-Peaks-like hotel.

After getting settled in, the organizers had the hotel generously arrange free food and drink in the hotel’s conference room, and the aforementioned conservation resumed for hours.

The organizers had worked with the town’s local government to arrange the conference, so the talks all took place in the town’s beautiful theater, which was a short walk from the hotel. Upon entering the theater on the first morning of talks, attendees were greeted with coffee, snacks, and music that lifted the spirits. It brilliantly created an atmosphere that supported continuing conversation and camaraderie.

Even before any talks had occurred, the conference had all of the properties I described of those fresh, exciting, and revolutionary circles. Everyone I spoke to was passionate about their craft. Everyone wanted to build something beautiful. Everyone loved what they did—at least, enough to fly to Sweden from all across the globe, take a four hour train ride to a rural town, and spend several days surrounded by a bunch of (mostly) strangers.

But nobody felt like strangers. The morning after arriving in the town, there was friendly Brazilian jiu-jitsu sparring, lake swims, and many-hour-long conversations.

This is partly because of Internet familiarity, but it was also because of a completely unique null hypothesis about shared passions, ideas, and knowledge. It was safe to assume that a “stranger” knew about—for instance—the early game engine work of John Carmack, or the game technology work at RAD, or Casey Muratori’s Handmade Hero, or the work and streams of Jonathan Blow. And it was safe to assume that they had a passion about writing high-quality games, engines, tools, or other software largely from scratch, to push the boundaries of what is capable in software, and to produce results superior to those elsewhere in industry.

And because they had passion, they had spent thousands of hours of their own time practicing and refining their abilities. Many attendees were highly successful in shipping their own games or other software—turn around, and you might just happen to run into the creator of Teardown, or a programmer who works on the Jai compiler, or the creator of File Pilot!

This made communication pleasant, valuable for all parties, and highly efficient. The conference was socially energizing, rather than exhausting—even for a population as naturally introverted as programmers. It was unfortunate to go to bed each night, because you’d have to cut exhilarating conversations with great, talented, and personable friends short.

High Signal, Low Noise

On top of the excellent atmosphere and practicalities, the talks at Better Software Conference were stellar. The signal-to-noise ratio was unlike almost any conference I’d seen (the only comparable equivalents were Casey’s HandmadeCon in 2015 and 2016).

The conference kicked off with a phenomenal talk from Casey himself, breaking down the history of a nearly ubiquitous—perhaps mistakenly—paradigm in the software industry. The subsequent talks in the day featured insights from Dennis Gustafsson (creator of Teardown) on physics engine parallelization, Bill Hall (gingerBill, creator of Odin and programmer at JangaFX) on learning mathematical tools, and Vjekoslav Krajačić on the codebase of File Pilot. This was only the first day.

The selection of speakers and the talk quality was no happy accident—the organizers didn’t simply get lucky. If your speakers regress to the mean, then your content regresses to the mean.

What do high quality speakers want? First, to be surrounded by other high quality people—or in other words, high quality attendees. Second, they want freedom. Third, they want a platform. The conference organizers provided all three. First, by carefully inviting attendees. Second, by keeping the conference schedule highly flexible, without any talk time limits or required topics. Third, by streaming all talks freely online to the public, with excellent professional audio and video.

Most importantly, because high quality speakers want an excellent in-person audience, and to be surrounded by others they’d be interested in speaking with, if your attendees regress to the mean, then your speakers regress to the mean.

Euphemisms For Power

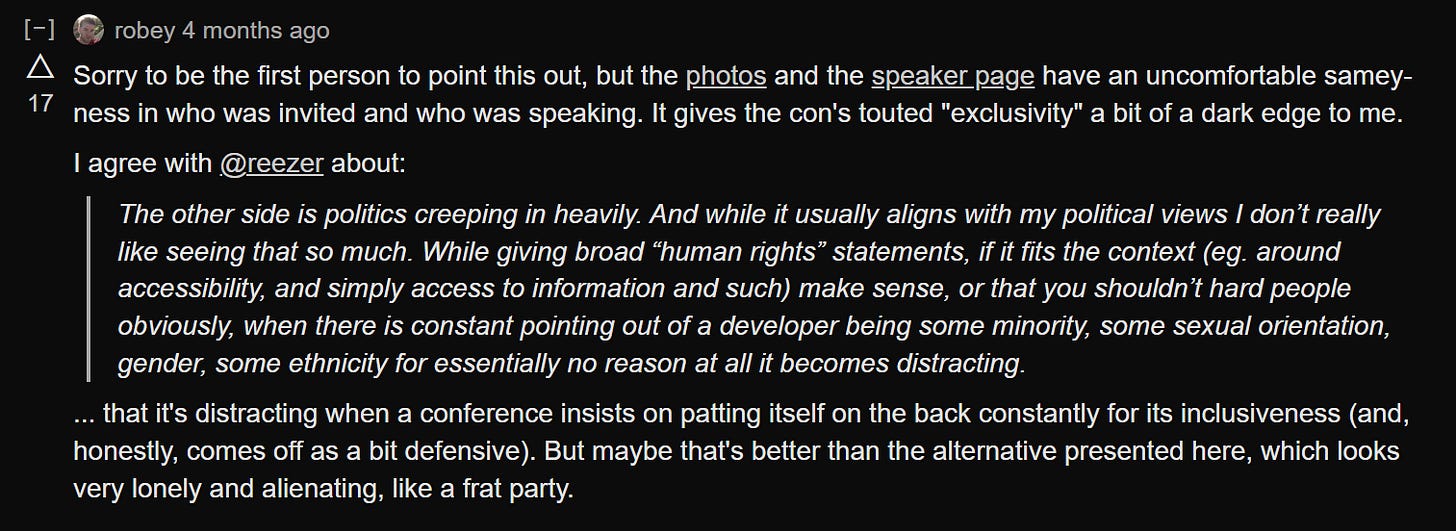

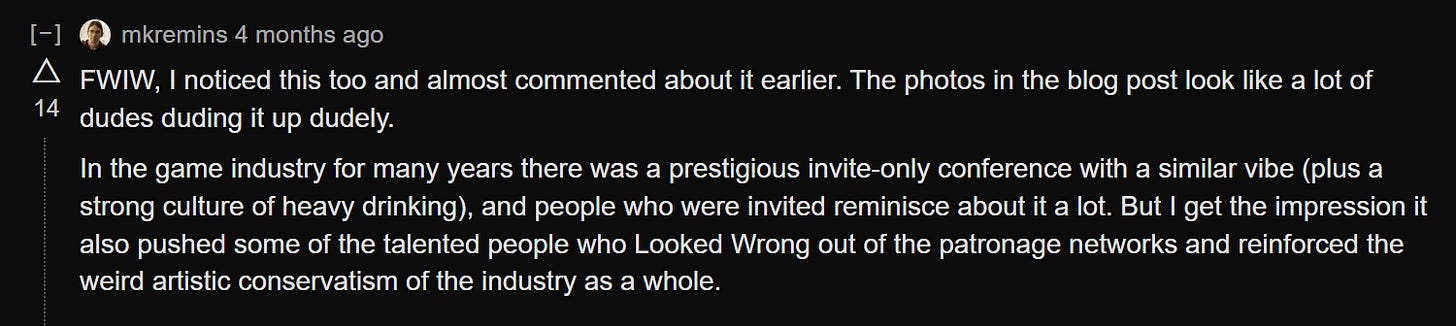

This invite-only structure is an unpopular way to execute a conference, here at the tail end of an era of “inclusivity”. Look no further than—and I’m sorry to do this—many online comments about the conference:

This is a small selection, but plenty similar comments exist. Of course, the conference was invite-only, and thus “exclusive”, but it wasn’t selecting for particular demographics, it was selecting for—and exclusively for—people who care about better software. It’s in the title. It’s why the conference wasn’t—despite the characterization—demographically homogeneous. Unsurprisingly, those more concerned with demographics than the topic of the conference wouldn’t typically make the cut.

Such rants about “sameyness”, or the conference looking like a “frat party”, or “dudes duding it up dudely”, are resentful, deranged tantrums that the demographics of a conference—a computer programming conference—attended by primarily Swedes, other Europeans, and Americans—do not match those that they’d prefer, which suggests a rather nefarious undertone.

The stories I’ve told in this post—which are a small sample of the same pattern which has repeated time and time again—teach an important lesson: obsession with growth will kill the spirit of an organization. Growth can manifest in a number of ways, but most importantly, it can manifest financially and influentially. Increasing growth in one of those two ways requires expanding a particular population—a userbase, a conference’s attendees, a follower count—which necessarily requires appeal to a broader population. In other words, the appeal must become less particular—more generic—to include a broader population.

Is this not inclusivity?

And so it comes full circle—the executive boardroom meeting discussing the maximization of growth—and the Internet “discussion” board “discussing” the maximization of inclusivity—are, fundamentally, discussing their desire for exactly the same outcome. The characteristic difference is that the boardroom is discussing it from inside an organization, and the Internet board is discussing it from outside an organization—but both desire, ultimately, growth. The terms they use may differ, yes—both groups use the appropriate language to maximally signal virtue to those from whom they desire social approval—but in substance, it is the same.

Furthermore, to desire financial growth and influential growth is to desire power—to desire that most of all is to have lust for power.

But for someone who is primarily concerned with craft, or the creation of beauty, and would rather financial gain and influence come as second order effects of that, this lust for power is detrimental to their whole purpose. It kills their communities, their organizations, their companies, their teams, and thus detracts from their already-difficult work.

This is why careful selection of people is critical, and this is why it works. In many cases—for example, in that of Usenet—this selection is informal and organic. In other cases, like that of the invite-only Better Software Conference, it was formalized. Both work, though formalization can aid the longevity of an organization as it was intended.

The reason I chose to write this post is that this conference was one of the best experiences of my life, but it was also an extremely unique experience. My experience is that the overwhelming number of companies, communities, conferences, and meetups do not fit this description. Most of them are Usenet—after Eternal September. I find that highly undesirable; the Better Software Conference provides a blueprint to build companies, communities, conferences, or other organizations which are highly fruitful and desirable.

The organizers of the Better Software Conference—beyond doing an excellent job planning practical necessities, like travel, lodging, and food—and doing a phenomenal job providing high quality audio & video and an excellent presentation space for speakers—understood that people are not fungible. They understood that—to put on a great conference—you need great people, together, with a platform, space, and ample free time.

When put like that, it sounds simple. And yet almost nobody does it. After all, that’s the philosophy of better software: Do the simple thing that solves the problem, that nobody else is thinking about.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing. Thanks for reading.

-Ryan